The U.S. Department of the Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control announced three vessels and shipping companies being sanctioned for violating the Russian oil sanctions on Thursday, only a few days after Treasury began a separate, larger probe of approximately 30 ship management companies covering 100 vessels suspected of violating a price cap on Russian oil.

“Shipping companies and vessels participating in the Russian oil trade while using Price Cap Coalition service providers should fully understand that we will hold them accountable for compliance,” said Deputy Secretary of the Treasury Wally Adeyemo in a statement on Thursday. “We are committed to maintaining market stability in spite of Russia’s war against Ukraine, while cutting into the profits the Kremlin is using to fund its illegal war and remaining unyielding in our pursuit of those facilitating evasion of the price cap.”

But as the Treasury seeks to cut off the Kremlin’s access to oil profits, its hunt for crude tankers and shippers violating OFAC guidelines is revealing complexities in its own guidelines and a murky marine industry.

The shipping entities identified on Thursday were United Arab Emirates-based. The vessels were Kazan Shipping Incorporated’s Kazan, Progress Shipping Company Limited’s Ligovsky Prospect, and Gallion Navigation Incorporated’s NS Century. But while those ships are now UAE-based, Matthew Wright, lead analyst of freight at marine intelligence firm Kpler, tells CNBC the location of where the company is based may be different from the location of the beneficial owner. In this case, Wright says the beneficial owner is likely still Russian-based.

“Based on the history of these fleets, these vessels were all owned and operated by Sovcomflot,” Wright said. “Management of all the Sovcomflot ships was transferred to Sun Ship Management in March/April 2022 when their offices in Europe were closed. Those three companies are now managed by a new manager called Oil Tankers SCF Management but it’s just another name. Ownership hasn’t changed since 2006. They’re not part of either the dark or grey fleet really as I consider them still Russian-owned.”

This is just one example of the murkiness within the Russian oil trade. The probe against 30 shipowners begun earlier this week reveals how identifying and finding proof of vessels traversing the oceans with sanctioned oil is not as straightforward as suggested by initial headlines covering the Treasury allegations. These companies received warning letters from the government about activity deemed suspicious and requests for documentation. There are grey areas in the U.S. government’s Russian oil guidelines, though the efforts can ultimately lead maritime investigators to the truth.

In the U.S. Treasury’s “Preliminary Guidance on Implementation of a Maritime Services Policy and Related Price Exception for Seaborne Russian Oil,” ship owners are under a Tier 2 category. According to the Treasury, this group within the maritime industry are “actors who are sometimes able to request and receive price information from their customers in the ordinary course of business.”

If a ship owner is unable to obtain such pricing information, according to the Treasury’s guidelines, the Tier 2 actors (ship owners) need to request “customer attestations” where their charter customers pledge in a document they will not purchase seaborn Russian oil above the price cap.

This document could provide a “safe harbor” for ship owners who are relying on that customer’s “attestation” to comply with sanctions. This safe harbor is also extended to the ship insurance companies.

“Ship owners rely on the charterer to provide ample proof that the Russian oil on board the vessel has been sold below the price cap,” said Andy Lipow, president of Lipow Oil Associates. “The sanctions can easily be circumvented if a dishonest charterer presents documents that falsify the true cost of the oil.”

Lipow said one clue to suspicious paperwork is a price of oil that is well below the market, selling Russian crude oil in Asia today at $50 per barrel when Brent is trading at $80.

“That is a red flag,” Lipow said.

Based on the safe harbor, if the ship owner or management company can be absolved of wrongdoing, the documents can still lead Treasury to the charterer.

The U.S. Treasury told CNBC it does not comment on current investigations.

A breakout of the Russian oil trade by Kpler shows around 30% of Russian exports from Western ports are still using commercial shipping with beneficial ownership within the European Union.

Wright said this “dark fleet” is comprised of vessels typically 20 years and older which have loaded or predominantly loaded Venezuelan or Iranian cargoes in the last few years.

“There is often some evidence that they have been disguising their activities by turning off their AIS, but not in all cases,” said Wright, referring to the automatic identification system used by marine vessels to track location. “Ownership is often opaque and the operator does not engage in standard commercial shipping outside of operating these vessels.“

There are also “grey fleet” vessels sold since the Russian invasion of Ukraine with the aim of transporting Russian exports and avoiding sanctions. These vessels, according to Wright, have had EU ownership.

“Most vessels have been sold by owners based in Europe to owners who were not previously active in the tanker market,” he said. “The owners are based mainly in Hong Kong, China, India, and the UAE.”

The price cap rules state that exports of Russian crude or refined products on EU-owned, insured, or serviced tonnage must be below the relevant price cap.

Since July, Wright says most exports from Russia are assumed to be above the caps, yet a large number of ships from within the EU continue to trade. This is because of the way Russian crude is traded.

“It is very likely vessels loading Russian cargoes that are EU-owned will have documentation showing a crude trade below the price cap, even if the cargo was actually traded above the price cap,” Wright said. “This is because a charterer or middleman will have traded it at a price that can be shown to the owner as part of a wider trade with the final buyer. The (vessel) owner is unlikely to have any evidence to the contrary.”

Vessel owners do not produce these documents, he said, but are provided with these documents by the charterer.

“The vessel owners are merely the custodians of information provided to them,” Wright said.

Beks Shipmanagement & Trading confirmed to CNBC it is among the companies that received warning letters from the Treasury this week and is sending documents to the government. The company had been identified in earlier press reports, though Treasury declined to specify companies to receive letters.

In an email to CNBC, the company rejected the Treasury’s allegations. “Despite the fact that the U.S. Treasury Department requested voyage details from 30 different ship management including 100 vessels, it is an obvious bad faith and reputation damaging purpose that only our management company was mentioned in the news recently circulated in the media,” a Beks spokesperson wrote.

The company, based in Turkey, announced in October the deployment of SpaceX’s Starlink satellite connectivity system across its fleet of 40 bulkers and tankers for enhanced vessel tracking.

“Our vessels are traded worldwide with their tracking system always switched to the on position. We employ our vessels by abiding (by) all international laws and regulations without breaching any sanction regime,” the company wrote in the email.

Beks said it has been conducting due diligence procedures on all of its voyages as well as carrying out the necessary sanction checks with its London-based lawyers.

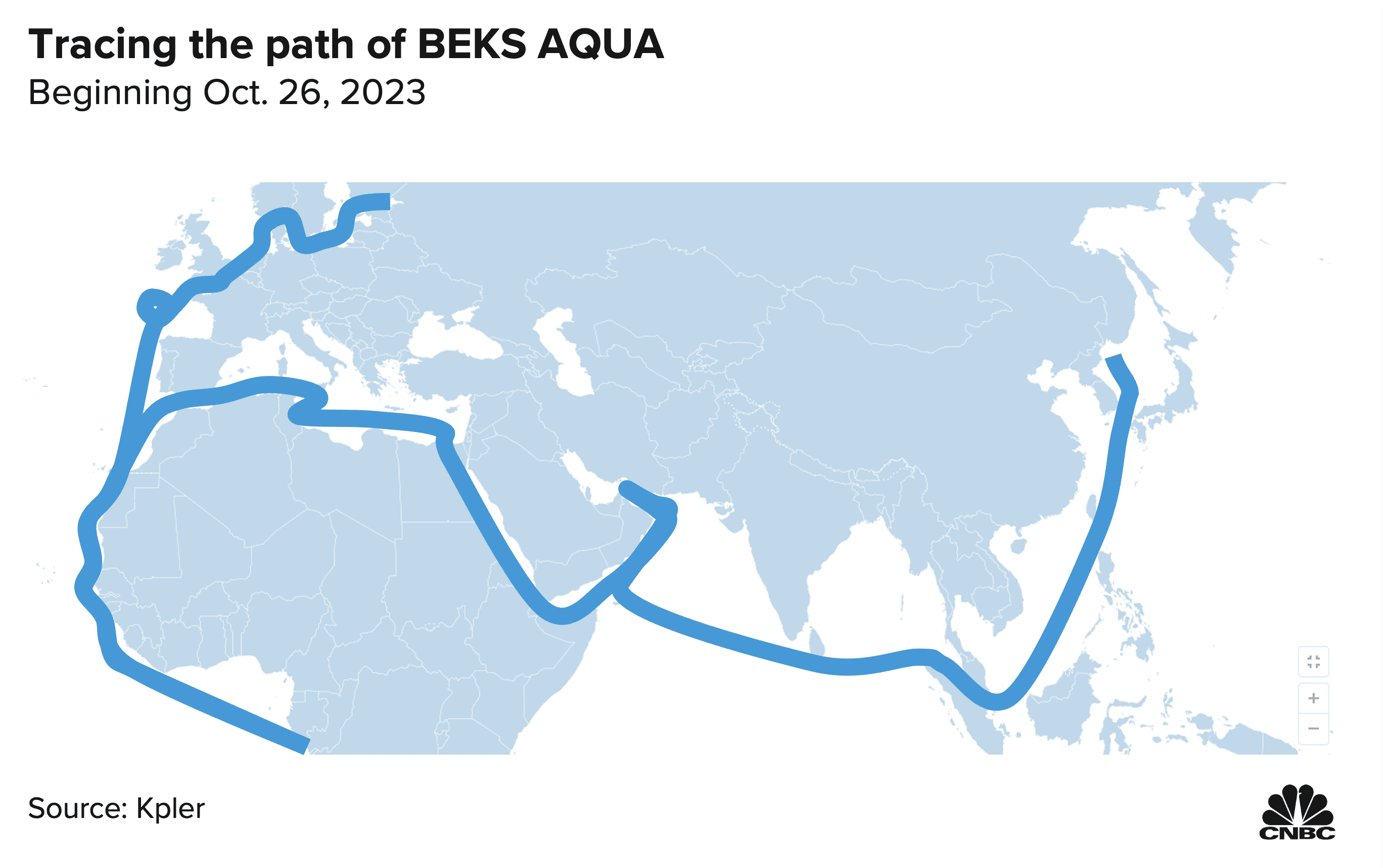

According to Kpler, Beks Shipmanagement’s fleet had numerous tanker port calls to Russia since the start of sanctions on February 24, 2022. One example is the oil products tanker Bek Aqua.

Kpler was able to track the travel of the tanker using the tanker’s satellite beacons through the AIS short-range coastal tracking system currently used on ships.

The tanker Beks Aqua arrived at the Russian Port of Nakhodka on Oct 26 and was loaded with either diesel or Naptha on November 1. The vessel then arrived at the Port of Singapore on November 10 and departed empty on November 14.

But following the satellite data doesn’t allow for understanding of contract prices.

“While we can track the vessel’s journey from Russia to Singapore, unless we have the sales contract, we do not know the price the oil product was purchased for,” Lipow said. “The only fact we have is companies like Beks Shipping are employed to move Russian oil. It is possible that someone filed false paperwork with the shipowner. This is why tracking the Russian oil sanctions is not straightforward,” he said.

Beks Shipmanagement said the requested voyage details will be provided to the U.S. Treasury with full transparency.

Explore our curated content, stay informed about groundbreaking innovations, and journey into the future of science and tech.

© ArinstarTechnology

Privacy Policy