Vaccines rile up the immune system against pathogen invaders. But in autoimmune diseases, the immune system becomes the enemy. Scientists have now figured out a way to tamp down this self-destructive response in mice by attaching sugars to molecules that provoke immune cells. This “inverse vaccine,” reported this month in Nature Biomedical Engineering, could potentially lead to new ways to combat autoimmune diseases such as multiple sclerosis (MS) and lupus.

“It’s a strong piece of work,” says Lawrence Steinman, a neuroimmunologist at Stanford Medicine who wasn’t connected to the study. The work, he says, offers “a cool new way” to potentially defuse self-destructive immune attacks. But Steinman and others caution that many other promising methods for taming the immune system in autoimmune diseases have faltered.

The immune system responds to molecules—or pieces of them—known as antigens. Most of the time they come from dangerous invaders like viruses and bacteria. But some immune cells react to self-antigens, molecules from our own cells. And in autoimmune diseases, these misguided immune cells turn against patients’ own tissues.

For more than 50 years, researchers have been trying to stop this internal war by restoring the body’s tolerance for its own antigens. They succeeded in experimental animals. In mice with an MS-like condition called experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), for instance, the immune system attacks the myelin insulation around nerves. Injecting myelin protein fragments into the rodents coaxes their immune systems to leave the myelin alone. But no tolerance-inducing strategy has performed well enough in people to receive approval as a therapy.

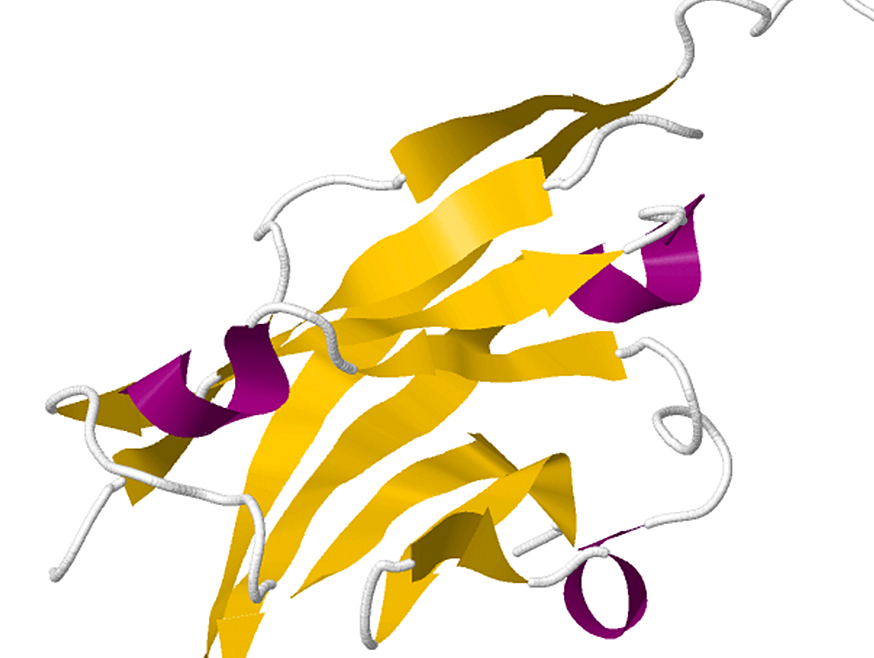

A team led by immunoengineer Jeffrey Hubbell, immunologist Andrew Tremain, and biomedical engineer Rachel Wallace of the University of Chicago has been exploring a new approach: directing potential self-antigens to the liver. The organ is crucial for establishing tolerance. Immune cells there pick up self-antigens and then stifle T cells that could target these molecules. The researchers came up with a way to steer antigens to the liver by affixing them to a chain of sugars.

When researchers inject an egg white protein into mice, it normally spurs a strong immune reaction. To gauge the capability of their approach, Hubbell and colleagues first asked whether it could curb this response. The team injected the protein into mice and then gave the animals three doses of the antigen attached to the sugar chain. When the scientists later analyzed the rodents’ lymph nodes and spleen, they found that the inverse vaccine weeded out and suppressed T cells that targeted the protein. These changes “all work together to reestablish immune balance,” Wallace says.

But the immune response to an egg protein isn’t an autoimmune reaction. So the team next investigated whether the approach worked against EAE, which researchers can induce in mice. An inverse vaccine composed of the sugar chain carrying a fragment of a myelin protein prevented mice from developing the disease, the scientists found. And a sugar-antigen combo that targeted a different myelin protein forestalled relapses in mice with a version of EAE that resembles a form of MS whose symptoms wax and wane.

An inverse vaccine’s ability to turn off a specific antigen response makes it a promising alternative to current autoimmune treatments, which more broadly suppress the immune system and leave patients vulnerable to infections and cancer, Hubbell says.

“The method they use is promising and potentially can induce better tolerance,” says neurologist and neuroimmunologist A.M. Rostami of Thomas Jefferson University. But he notes that one reason previous attempts to spark tolerance failed is that researchers don’t know which self-antigens are being attacked. The inverse vaccine strategy doesn’t overcome that problem, he says. “Is this approach applicable to human disease in which we don’t know the antigen? We don’t know.”

Immunologist Jane Buckner of the Benaroya Research Institute shares his mixed response to the new approach. She calls it “a good first step,” but adds that the mechanisms that produce tolerance remain poorly understood.

A company Hubbell co-founded recently conducted a phase 1 trial to establish the safety of this approach in people with celiac disease, whose immune systems overreact to gluten in bread and other foods. The patients suffered no serious side effects, and the results hinted that the treatment reduced symptoms. The company has now launched a phase 2 study in celiac patients to gather further data on effectiveness, as well as a phase 1 trial of a myelin-based combination in patients with MS.

Whether the approach will finally achieve the long-sought goal of spurring tolerance in patients remains to be seen, Steinman says. “But I hope that someday somebody is going to get it right and change the world.”

Explore our curated content, stay informed about groundbreaking innovations, and journey into the future of science and tech.

© ArinstarTechnology

Privacy Policy