Researchers have coaxed human stem cells to form early-stage human kidneys in pigs—the first time a human organ has been produced in another animal. The advance, stem cell researchers say, could bring pig-grown human organs closer to reality, offering a new solution for the many people on waitlists for transplants.

“This is a big step forward in the field,” says developmental biologist Juan Carlos Izpisúa Belmonte of Altos Labs, whose team has experimented with growing human stem cells in other species but who was not involved with the current work. The kidneys the scientists generated weren’t intended to be transplanted into patients, but Izpisúa Belmonte says the new research “hints that the ultimate goal of developing human organs in other mammals might be possible.”

Transplant surgeons seeking to address the scarcity of human organs have already implanted pig kidneys and hearts into a few brain-dead people and terminal patients in experimental procedures. Although these came from pigs that had been genetically modified so their organs would avoid immediate rejection by the human recipients, this strategy would still likely require lifelong treatment with immune-suppressing drugs. Growing human organs in pigs instead is an alluring alternative for transplants because patients could receive organs derived from their own stem cells, which shouldn’t spark an immune attack.

Izpisúa Belmonte and other researchers have made some advances toward this goal. For instance, regenerative cell biologist Mary Garry of the University of Minnesota and colleagues inserted human stem cells into early pig embryos that had been genetically altered to prevent the growth of specific tissues. When implanted into a surrogate mother pig, the embryos used the human cells to build some of the tissues they couldn’t generate themselves. So far, the researchers have shown that these pig embryos can grow human muscle and blood vessel lining. But no one has been able to induce these embryos to make organs, which contain multiple cell types.

A team led by stem cell biologists Liangxue Lai, Zhen Dai, Miguel Esteban, and Guangjin Pan of the Guangzhou Institute of Biomedicine and Health thought they knew why—the human stem cells were wimpy and out of sync with their pig cell neighbors. To fix the first problem, the researchers genetically tweaked the human cells to increase the activity of two genes. Cells in an embryo vie with one another, and this change boosted the human cells’ ability to compete with pig cells and deterred them from committing suicide.

The second problem occurred because the human cells were developmentally ahead of their pig equivalents. To overcome that obstacle, the scientists grew the human cells in a newly devised culture medium that returned them to an earlier developmental stage. As a result, the human cells could better integrate with neighboring pig cells.

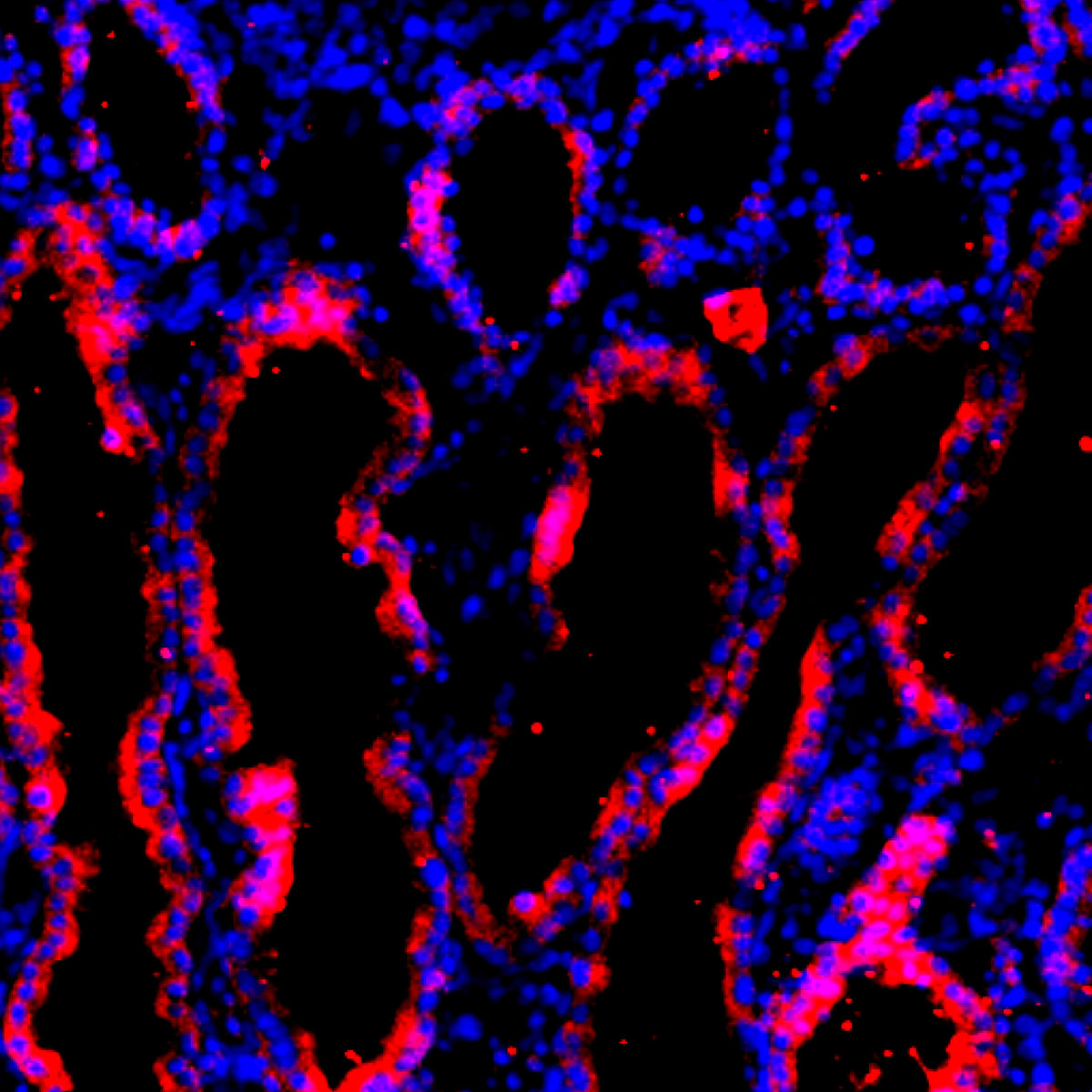

The scientists then inserted these upgraded human stem cells into pig embryos that had been genetically modified to lack the ability to grow a kidney. After implanting the embryos into surrogate mother pigs, the researchers allowed them to develop for about a month and then removed them for analysis. A few of the pig embryos contained primordial human kidneys, the team reports today in Cell Stem Cell. Up to 65% of the cells in these organs were human, indicating the stem cells had spawned kidney cells in their porcine surroundings.

These kidneys are a lab first, but scientists have a lot more to do before they can create organs that are ready for transplantation into patients. Because the team stopped the embryos’ progress after about a month, they grew temporary kidneys that only operate for a few weeks early in development. Another set of kidneys arises later and functions for the rest of life—these are the organs needed for transplantation. In addition, scientists want to increase the percentage of human cells in the organs. Kidneys harboring pig cells would provoke immune attacks if they were inserted into patients.

Growing human organs in pigs also raises ethical issues. Human cells could end up in the animals’ brains or reproductive systems, for example, potentially altering their mental abilities or even giving rise to sperm or eggs that have human genes. The scientists did find some human-derived cells in the embryos’ brains and spinal cords, but they didn’t detect any in the reproductive system. To move the transplant strategy forward, researchers may have to make additional genetic alterations to the human stem cells to prevent this infiltration, Esteban says.

The approach Esteban and his colleagues followed to bolster the stem cells before insertion into the embryos “is very sound,” says stem cell biologist Zhongwei Li of the University of Southern California. But questions remain about the human kidney cells in the embryos. “Are they good kidney cells? We don’t have the evidence.” And the big question, Li adds, is whether researchers can make an adult-stage kidney.

Garry, who co-founded a company that is trying to produce human organs in pigs, cautions that the genetic modifications the researchers made to the human stem cells can lead to cancer. She also wants to see further analysis of the human cells in the kidneys and of the organs’ function. “It is imperative to prove that the developing kidney is human and that these pigs survive until birth and beyond.”

Esteban says the researchers plan to let similar embryos with human stem cells develop for a longer time to determine whether the adult-stage kidney forms. He cautions that the timetable for producing transplantation-ready organs is uncertain. But he’s optimistic. “I think that within a decade this may be a reality.”

Explore our curated content, stay informed about groundbreaking innovations, and journey into the future of science and tech.

© ArinstarTechnology

Privacy Policy